Neurology & Neurosurgery FAQs

Geriatric vestibular syndrome in dogs

What is a geriatric vestibular syndrome?

Geriatric vestibular syndrome, or idiopathic vestibular syndrome, is a common neurological disorder of elderly (8 years plus) dogs, causing a sudden disruption of the animal’s balance. The disorder arises from an abnormal function of the peripheral portion of the dog’s balance system which consists of the inner ear and the peripheral vestibular nerve. The animal’s brain in these cases is not affected. This is a benign condition of unknown origin.

What are the clinical signs?

Clinical signs vary from mild to very severe. Typically, the dog exhibits head tilt, spontaneous movement of the eyes (nystagmus), circling to one side and balance problems while walking. Animals tend to drift and fall towards one side of their body. In more severe cases, the dogs are not able to stand up or they can constantly roll to one side. Dogs can also show nausea and/or vomiting.

How is geriatric vestibular syndrome diagnosed?

Geriatric vestibular syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion. First, the neurologist performs a neurological examination to confirm that the neurological localisation fits with the suspected diagnosis. Secondly, all necessary blood tests and blood pressure measurements are performed to exclude potential causes for the balance problems. Thirdly, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examinations may be performed to rule out possible brain diseases that could cause very similar neurological signs. In case of geriatric vestibular disease all diagnostic investigations show normal results.

Can geriatric vestibular syndrome be treated?

Geriatric vestibular syndrome is managed with supportive treatment, which includes hospitalisation for few days if the animal is not able to walk, supportive therapy with intravenous fluids, medication against vomiting and walks with support.

Quality of life and prognosis?

Geriatric vestibular syndrome has a good prognosis. Dogs usually spontaneously recover from this balance disorder within a few days. However, full recovery might sometimes take a few weeks. Sometimes mild neurological deficits (such as mild head tilt) might remain for the lifetime, but they do not interfere with the dog’s quality of life.

Acquired myasthenia gravis

What is acquired myasthenia gravis?

Myasthenia gravis is a disease of the neuromuscular junction leading to exercise intolerance and muscular weakness. Myasthenia gravis may affect both dogs and cats. Certain dog breeds (Newfoundland, Great Dane, Golden Retriever, Labrador Retriever, Akita, Scottish Terrier), and cat breeds (Abyssinian and Somali) are more prone to develop acquired myasthenia gravis, but any breed might be affected. Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease, which may occur spontaneously or secondary to other diseases (i.e., neoplasia).

Acquired myasthenia gravis is divided into three subtypes: generalised, focal and fulminating. Depending on the subtype, the clinical signs vary from very mild to severe.

What are the clinical signs?

A typical clinical picture of a generalised myasthenia gravis is exercise intolerance. Usually, the animal can start walking normally for a certain amount of time, which varies from case to case. After some exercise the animal becomes weak in the hind limbs and eventually sits or lays down to rest for few minutes. The animal may also show pronounced drooling and abnormal breathing sounds. After getting some rest, usually the animal can stand up and walk again until becoming exhausted again.

Unfortunately, the oesophagus may be affected as well, leading to a condition called megaoesophagus (abnormal enlargement of the “food pipe” which connects the larynx to the stomach). Megaoesophagus predisposes to food regurgitation which can lead to aspiration pneumonia, a serious condition affecting the lungs. Sometimes the animal has difficulties to swallow the food.

How can myasthenia gravis be diagnosed?

There are few tests available to diagnose myasthenia gravis, including an edrophonium injection test, a specific blood antibody test and electrodiagnostic investigations. Usually a combination of these tests is performed to confirm the diagnosis. If myasthenia gravis is suspected, a neurologist carries out imaging to inspect the oesophagus and screen for neoplasia.

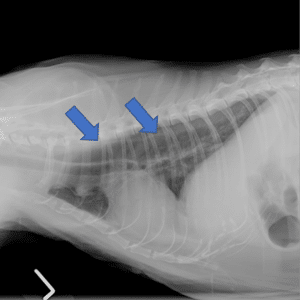

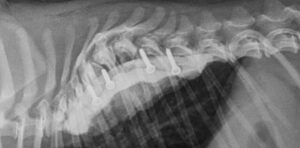

Fig. 1. Radiographs. Thoracic neoplasia – thymoma (blue arrows) – causing acquired myasthenia gravis in a cat.

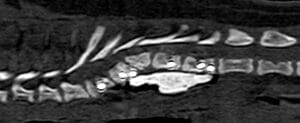

Fig. 2. Megaoesophagus (blue arrows) in a cat suffering from acquired myasthenia gravis.

Can myasthenia gravis be treated?

Yes, the treatment usually consists of prolonged medical treatment with drugs that enhance the signal transmission between the nerves and the muscles and prevent the exhaustion of the neuromuscular junction. Immunosuppressive drugs may be needed.

In addition, the underlying cause (such as neoplasia) might need to be addressed surgically.

Quality of life and prognosis?

The prognosis for the acquired myasthenia gravis is guarded to good. Megaoesophagus and problems with swallowing may lead to serious complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, which can be detrimental to the animal. However, dogs and cats might recover completely from acquired myasthenia gravis. A well-designed medication plan and dedicated animal care is crucial in successful treatment of myasthenia gravis.

Canine steroid responsive meningitis arteritis (SRMA)

What is steroid responsive meningitis arteritis (SRMA)?

SRMA is an immune mediated inflammation of the meninges and associated blood vessels, leading to severe neck pain.

Which animals does it affect?

Typically SRMA affects young (few months to 2 years old) dogs. Certain breeds (Beagle, Boxer, Swiss Mountain Dog, Jack Russel Terrier, Duck Tolling Retriever, Weimaraner, Border Collie, Whippet, English Springer Spaniel) have predisposition to this disease.

What are the clinical signs?

Dogs affected by SRMA exhibit acute or chronic onset of severe neck pain, low head carriage, reluctance to move, stiffness of the neck musculature, fever.

How is SRMA diagnosed?

A neurologist will perform the necessary blood tests, diagnostic imaging of the neck and a cerebrospinal fluid tap. The key to SRMA diagnosis is the cerebrospinal fluid examination. Typical findings include: increased white blood cells and protein count.

How is SRMA treated?

The condition is successfully treated with immunosuppressive treatment (usually corticosteroids).

Quality of life and prognosis?

SRMA is a disease with excellent prognosis. Usually dogs are free of symptoms within few days after initiation of treatment. However, a long treatment over 4-6 months is required to prevent the relapses. Although one third of the patients may still develop the reoccurrence of the clinical signs, it can be successfully managed by re-initiating the immunosuppressive treatment. Dogs rarely suffer from relapses of SRMA once they reach 2 years of age.

Canine Idiopathic Epilepsy

What is this?

The idiopathic epilepsy is a recognized disease very common in dogs and it is characterized by episodes called seizures. These seizures are the manifestation of uncontrolled brain activity and the cause of this alteration of the brain function remains unknown.

How can I recognize a seizure?

A seizure is usually divided in three parts, known as: pre-ictal, ictal and post-ictal phases. During the pre-ictal phase the animal may be disorientated or looking for attention.

The ictal phase is the proper seizure. During this phase, an animal is commonly unconscious and may show tonic-clonic involuntary movements of the muscles of the limbs, balance deficits, urination, defecation and hypersalivation. The ictal phase may last from a few seconds to a few minutes. Finally the post-ictal phase is the period where an animal returns to normality. This phase could last minutes, hours or days and dogs may show subdued mental status, vision deficits (blindness), changes in behaviour and disorientation.

How is canine idiopathic epilepsy diagnosed?

The diagnosis is made by ruling out other diseases leading to seizure activity. Commonly, canine idiopathic epilepsy tends to occur in animals between 6 months and 5 years of age and certain breeds are predisposed to this disease. Commonly the investigations performed to diagnose canine idiopathic epilepsy include blood sampling to check for underlying metabolic/systemic disorders, MRI scans of the dog’s brain and, in some occasions, cerebrospinal fluid analysis and DNA testing.

Is there any treatment?

Yes, there is a wide range of anti-epileptic medications to treat canine idiopathic epilepsy. The goal is to reduce the seizures’ frequency and severity. The anti-epileptic therapy is tailored to best control the dog’s seizures.

Quality of life and prognosis?

Anti-epileptic therapy may effectively reduce the seizures’ frequency and severity and dogs may have a good quality of life. However, about 20-30% of dogs may unfortunately become unresponsive to the anti-epileptic medications and may continue experiencing a number of seizures.

Feline Idiopathic Epilepsy

What is Idiopathic epilepsy?

Feline idiopathic epilepsy is defined as multiple seizures occurring without any identifiable cause. The most common age of presentation is between 7 months and 7 years.

How can I recognize a seizure?

The episodes are divided in pre-ictal, ictal and post-ictal phases. During the pre-ictal phase cats may show alteration of normal behavior, hiding or looking for attention, vomiting, nauseas or even aggression. The ictal phase is characterized by bilaterally symmetrical tonic, clonic or tonic–clonic movements: cats may fall down on one side and have alternating periods of extension and flexion of the limbs. These episodes are also normally accompanied by loss of consciousness, hypersalivation and vocalization.

The post-ictal phase is the resting period after the involuntary movements and can be characterized by hiding, blindness, disorientation and/or incoordination.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is made by ruling out other diseases leading to seizure activity. Commonly, the investigations performed to diagnose feline idiopathic epilepsy include blood sampling to check for underlying metabolic/systemic/infectious disorders, MRI scans of the cat’s brain and, in some occasions, cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Can it be treated? What is the prognosis?

Anti-epileptic therapy may effectively reduce the seizures’ frequency and severity and cats may have a good quality of life. Unfortunately, some cats may become unresponsive to the anti-epileptic medications and may continue experiencing a number of seizures.

Hydrocephalus

What is hydrocephalus?

Hydrocephalus is an active distension of the ventricular system of the brain. The hydrocephalus can be classified as congenital or acquired. The congenital form is an inborn condition and is overrepresented in these breeds: Maltese, Yorkshire terrier, English bulldog, Chihuahua, Lhasa Apso, Pomeranian, toy poodle, cairn terrier, Boston terrier, pug dog, and Pekingese.

Congenital hydrocephalus may not cause any clinical sign until adulthood.

Acquired hydrocephalus is commonly caused by obstruction of the cerebrospinal fluid flow or can be secondary to inflammatory/infectious diseases.

Some frequent clinical signs associated with hydrocephalus include abnormally shaped skull (i.e. dome-shaped head), strabismus, difficulties with training, balance deficits, altered mentation, behavioural changes, vision difficulties and seizures.

How can hydrocephalus be diagnosed?

Careful clinical and neurological examinations are needed. If hydrocephalus is suspected, advanced imaging of the brain should be carried out (see Fig. 1 & 2)

Can hydrocephalus be treated?

Therapy for hydrocephalus can be medical or surgical.

Medical therapy may stabilize or improve the clinical signs in the short term, but often it is not successful in the long-term. Surgical treatment (ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement) is generally recommended when an animal is showing worsening clinical signs or shows no evidence of improvement or deteriorates when being treated medically (Fig. 3).

Quality of life and prognosis?

After surgery, a number of dogs show sustained improvement, but serious post-operative complications may occur.

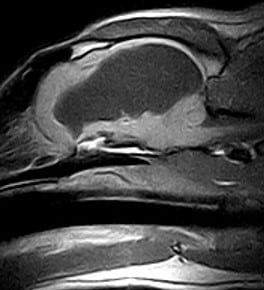

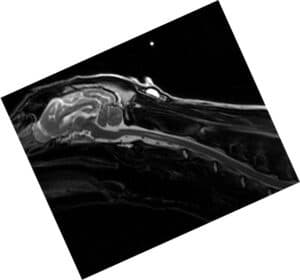

Fig. 1. Pre-contrast T1-weighted sagittal MR image of a dog with a marked enlargement of a lateral ventricle.

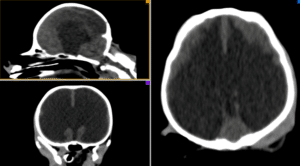

Fig 2. Computed Tomography (CT) images of a dog with generalised marked enlargement of the ventricular system

Fig 3. 3D CT reconstructed image of a dog after placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt

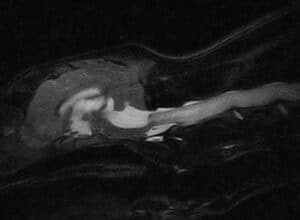

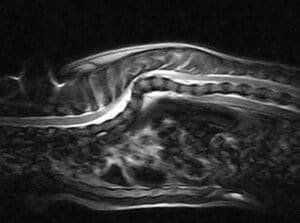

Fig 4: T2-weighted sagittal MR image of a young Labrador revealing a marked generalised hydrocephalus and cervical syringomyelia.

Fig 5: T2-weighted sagittal MR image of the dog in Fig 4 one year after the placement of the ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Note the resolution of the hydrocephalus and the marked reduction of the cervical syringomyelia.

This video shows the placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt in a dog affected by hydrocephalus.

Brain Tumours

What are the most common clinical signs?

Brain tumors tend to occur in a middle-age/old population of dogs. Common clinical signs include seizures, altered mentation, disorientation, circling and changes in behaviour.

How is it diagnosed?

The presumptive diagnosis is made with the help of advanced imaging of the brain. Often, advanced imaging of the entire body is necessary to better understand the nature of the brain neoplasm.

Can brain tumours be treated? And which is the prognosis?

Some type of tumors can be surgically de-bulked. If the brain neoplasm cannot be accessed surgically, palliative treatment is usually pursued and consists of corticosteroid medications and, if possible, radiation therapy. Generally, the long term prognosis for intracranial tumours is poor but varies individually and depending of the type of the tumour.

Canine Spinal Arachnoid Diverticula (SAD)

What is this?

Spinal arachnoid diverticula (SAD) are focal dilations of the subarachnoid space, which can lead to a progressive damage of the spinal cord. The age of onset of clinical signs varies between a few months to 12-13 years. Pug dogs, Rottweilers, and French Bulldogs are the most common breeds affected by this spinal disease.

What are the clinical signs?

The most common clinical signs include weakness and un-coordination which can affect only the hindlimbs or all limbs, depending on the location of the SAD. Urinary and faecal incontinence may also occur whereas spinal discomfort is uncommon.

How is SAD diagnosed?

SAD is diagnosed with the help of advanced imaging (Fig 1).

Is there any treatment?

Yes, therapy may be medical or surgical. However, surgery has become the most widely accepted means of addressing SAD. In addition, one study suggested that surgical treatment might be superior to medical treatment in the management of subarachnoid diverticulum in dogs. Medical therapy would consist of administration of anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics (if necessary) and physio/hydrotherapy. Different surgical approaches have been described but none of the surgical techniques has been proven to be superior to treat canine SAD.

What is the prognosis?

Veterinary studies reported a successful short-term outcome in approximately 60-80% of dogs with spinal arachnoid diverticulum treated surgically. However, in one recent study, the long term outcome was graded as poor in about 85% of pugs affected by thoracolumbar subarachnoid diverticula. Recurrence of clinical signs can be as high as 66%.

This video shows a spinal surgery for the removal of a subarachnoid diverticulum in a young pug performed with our neurosurgical microscope

Canine idiopathic facial palsy

What is this?

This is a disease affecting one or both facial nerves in dogs. There is no cause for this disease.

How can I recognize facial palsy in dogs?

Facial palsy tends to affect middle-aged – old dogs. Dogs may show sudden onset of drooping of the ears and lips and decreased to absent blinking reflex (they cannot close the eyelids). Most dogs tend to have trouble keeping food in the mouth while eating. Some dogs may also exhibit balance deficits as facial palsy may occur together with vestibular disease.

How is canine idiopathic facial palsy diagnosed?

In order to presumptively diagnose idiopathic facial palsy, advanced imaging and blood work are commonly necessary to ruled out of causes of acute facial nerve dysfunction such as inflammatory/infectious diseases, neoplasia and hypothyroidism.

Is there any treatment?

There is no effective therapy for idiopathic canine facial palsy. Commonly, artificial tears to maintain the cornea(s) adequately lubricated is the only therapy.

Quality of life and prognosis?

The idiopathic facial palsy should not affect the dog’s quality of life. The prognosis for a complete recovery is guarded: in some dogs, spontaneous recovery has been described but it usually occurs within weeks to months. Some dogs may develop facial contracture (shortening of the facial muscles that may make the affected side of the dog’s face appear to be ‘lifted’ in comparison to the unaffected side). In most dogs affected by vestibular disease and facial palsy, the balance deficits tend to improve with time.

Canine Paroxysmal Dyskinesia

What is this?

This is a disease characterized by sudden onset episodes of painless abnormal, involuntary movements lasting from seconds to hours.

How can I recognize paroxysmal dyskinesia in dogs?

Typically, during an episode, dogs do not lose consciousness and may show sustained or repetitive muscle contractions/spasms of the limbs, spine and/or neck, muscle tremors, loss of balance and un-coordination. The episodes begin and end abruptly.

How is canine paroxysmal dyskinesia diagnosed?

It is always very helpful to have video recording of the episodes mainly to distinguish the paroxysmal dyskinesia from epileptic seizures. Depending on each case and the clinical suspicion, further investigations (i.e. blood work and advanced imaging of the dog’s brain) may be carried out.

Is there any treatment?

There is no definitive therapy for this disease which does not seem to be life threatening. In some forms of paroxysmal dyskinesias dogs may respond to gluten-free hypoallergenic diet therapy. Commonly, antiepileptic medications fail in reducing the frequency or duration of the episodes of dyskinesia in dogs.

Prognosis?

In some cases, the episodes may be self-limiting with many dogs improving over time (sometimes years). Unfortunately, some dogs fail to enter remission or to improve.

For more information about canine paroxysmal dyskinesia you may read this interesting article.

Congenital malformations of the thoracic vertebral bodies in dogs

What is this?

Dogs may suffer from a variety of congenital malformations of the thoracic vertebral bodies. These malformations may represent incidental findings, but may also be associated with varying degrees of spinal cord compression and secondary neurological dysfunction.

What are the clinical signs?

Dogs affected by congenital malformations of the thoracic vertebral bodies are commonly young and the brachycephalic “screw-tailed” breeds are overrepresented. Common clinical signs include progressive weakness and un-coordination of both hindlimbs, and sometimes spinal discomfort. Unfortunately, some dogs may become suddenly unable to use both hindlimbs.

How are congenital malformations of the vertebral bodies diagnosed?

The initial presumptive diagnosis may be achieved by a combination of signalment, clinical history, neurological findings and plain radiography. However, the final diagnosis is commonly made with the help of advanced imaging (CT & MRI) which helps identifying the degree of spinal cord compression and the presence of additional spinal disorders (see for example the subarachnoid diverticula) (Fig. 1, 2, 3). In addition, advanced imaging also helps in planning surgical therapy.

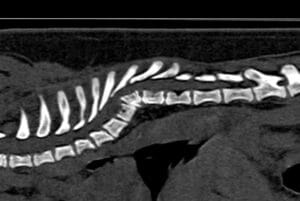

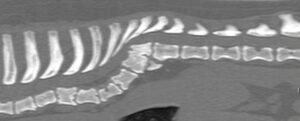

Fig. 1. Sagittal T2-weighted MR image of the thoracic spine of a young French Bulldog. Note the wedge vertebrae T5 and T6, the scoliosis and the spinal cord compression.

Fig. 2, 3: Sagittal CT images of the spine of two young pugs. Note the presence of vertebral body malformations with different degrees of scoliosis.

Is there any treatment?

Yes. Therapy for congenital malformations of the thoracic vertebral bodies can be medical or surgical. Medical therapy commonly consists of administration of anti-inflammatory medications (corticosteroids or NSAIDs), exercise restriction and, if necessary, analgesic drugs. Different surgical techniques have been described. The aims of the surgery are to achieve decompression of the spinal cord and to stabilise the abnormal spinal region.

At North West Veterinary Specialists, when possible, we perform spinal surgery to correct congenital malformations of the thoracic vertebral bodies as, in our experience and also as showed in the veterinary literature, medical therapy of this spinal disorder is associated with an unfavorable outcome and most dogs show progression of the neurological signs. We carry out a distraction-fusion technique through an intra-thoracic approach (Fig. 4, 5, 6, 7). This technique was ideated by Dr Massimo Baroni (Dipl ECVN)

Fig. 4, 5: Post-operative radiographs of the dog of Fig 2 after distraction/fusion technique through an intrathoracic approach.

Fig. 6, 7: Pre-operative and post-operative CT images of a young pug with wedge vertebra and associated scoliosis undergoing distraction/fusion technique through an intrathoracic approach. Note how the scoliosis has been partially corrected after surgery.

Canine Intervertebral Disc Disease

What is Canine Intervertebral Disc Disease?

Intervertebral disk disease, often referred to as “slipped disc” is a frequent cause of spinal disease in dogs leading to abnormal gait, weakness or, unfortunately, to paralysis.

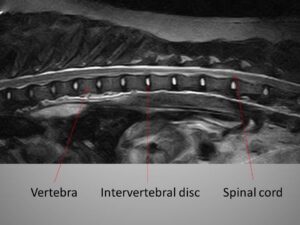

The intervertebral discs are in between the vertebrae and have a shock absorber function.

If the intervertebral disc degenerates, part of it may invade the vertebral canal and can compress the spinal cord and peripheral nerves.

Three types of intervertebral disc disease have been classified in dogs:

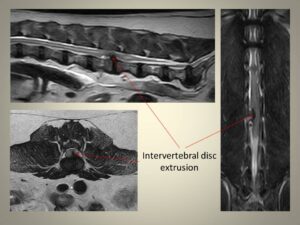

- intervertebral disc extrusion, type I

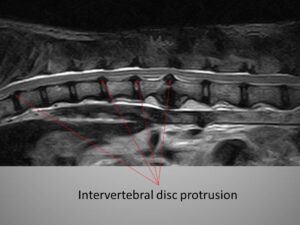

- intervertebral disc protrusion, type II

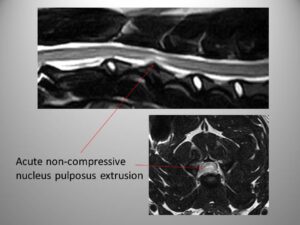

- acute non-compressive nucleus pulposus extrusion, type III

The intervertebral disc extrusion consists in the herniation of the intervertebral disc material within the vertebral canal that causes acute spinal cord and peripheral nerve damage.

Intervertebral disc protrusion is a chronic “bulging” of the intervertebral disc in the vertebral canal that causes chronic spinal cord and peripheral nerve damage.

The acute non-compressive nucleus pulposus extrusion is an extrusion of a small amount of non-degenerated intervertebral disc material that “hits” the spinal cord and dissipates in the vertebral canal.

How do I know if my dog has intervertebral disc disease?

A common sign of intervertebral disc disease is pain caused by the compression of the intervertebral disc to the spinal cord and spinal nerves. The neurological signs are influenced by the localization of the intervertebral disc disease and by the severity of the spinal cord damage. The dog could be reluctant to walk or may show more severe signs including paralysis (inability to use the limbs) with or without loss of the ability to feel the deep pain perception in the paws/limbs and urinary and faecal incontinence.

How is intervertebral disc disease diagnosed?

A complete neurological examination is needed to define which part of the spinal cord is affected and if and where advanced imaging needs to be performed. Our preferred advanced imaging technique for intervertebral disc disease is magnetic resonance imaging.

Which is the treatment for intervertebral disc disease?

Over the years several medical and surgical treatments have been proposed.

Dogs diagnosed with intervertebral disc disease showing mild spinal pain, or mild neurological deficits with no progression of the neurological signs could be good candidates for medical treatment based on pain relief medications and restricted physical activity commonly for 6-8 weeks. Medical treatment is considered non-successful if the dog’s pain persists despite the pain relief therapy and/or if neurologically the dog does not improve or deteriorates. Non-successful medical treatment leads to the surgical intervention. We recommend urgent spinal surgery in dogs that cannot walk at all. Different surgical techniques are used depending on the type and location of the intervertebral disc disease.

When will my dog go home after spinal surgery?

Common post-surgical hospitalisation time is between 3 to 7 days. However, this is subjective for every dog and, sometimes, longer hospitalisation time is required.

Nursing care and physiotherapy instructions will be fully explained to clients and also a written discharge note will be provided.

What is the prognosis?

Medical treatment for dogs with mild spinal pain or minimal neurological deficits has a fair to good prognosis. However, the risk of relapse and future neurological deterioration exists.

In surgically treated dogs, the prognosis mainly depends on the preservation of deep pain perception in the limbs/paws. If the dog at the time of surgery can still feel their paws, the prognosis for a recovery is commonly good.

Dogs that at the time of surgery have lost the ability to feel the deep pain perception in the affected limbs/paws have significantly less chances of recovery of the limbs function.

Dogs affected by intervertebral disc disease may unfortunately develop myelomalacia. Myelomalacia is a fatal condition that produces softening of the spinal cord which starts degenerating irreversibly. This condition is more likely to occur in the more severe cases (dogs without deep pain perception) but it may also occur in dogs with preserved deep pain perception.

Dogs that do not recover the ability to walk can still sometimes maintain a good quality of life using a dog wheelchair.

Below you can watch a video showing a spinal surgery (ventral slot technique) for the removal of an extruded intervertebral disc at the cervical spine in a French Bulldog. WARNING: this video contains intraoperative images that may offend some viewers.